Traduzione generata automaticamente

Mostra originale

Mostra traduzione

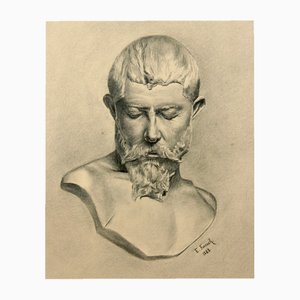

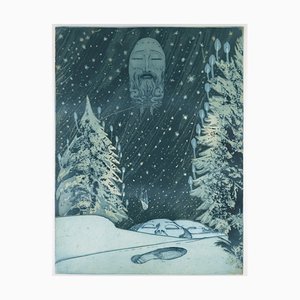

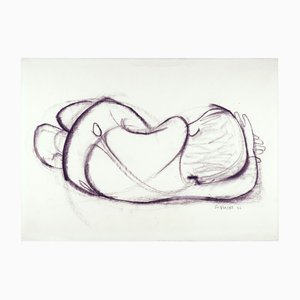

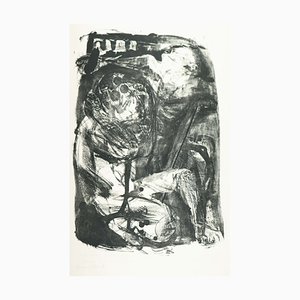

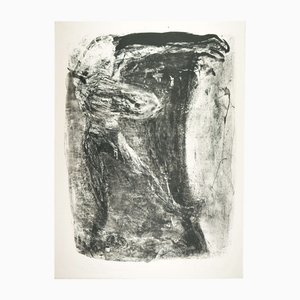

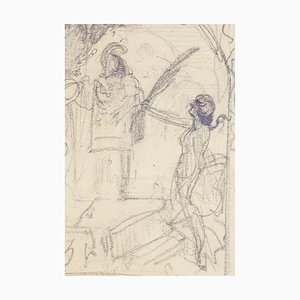

Lovis Corinth (1858 Tapiau - 1925 Zandvoort), Rudolf von Rittner as Florian Geyer, 1924 (Müller 854), drypoint signed in pencil. 20.4 × 14.2 (plate size), 37.7 × 30.6 cm (sheet size). Published by Karl Nierendorf, Berlin. Framed in a passepartout.

- Strong, precise impression. Frame a little bit rubbed and with two small damages.

Exposé as PDF

- Last man standing -

About the artwork

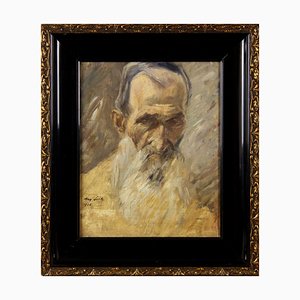

The knight is a leitmotif in Lovis Corinth's work, culminating in his Self-Portrait in Armour of 1914. Of all the paintings on this theme, Corinth most often depicted Florian Geyer. Descended from a Franconian noble family, he fought for the freedom of the peasants during the peasant wars of the Reformation, first diplomatically and then militarily, leading the legendary Schwarzen Haufen (Black Troops). The name derives from the black uniforms with which Geyer dressed the peasants willing to fight.

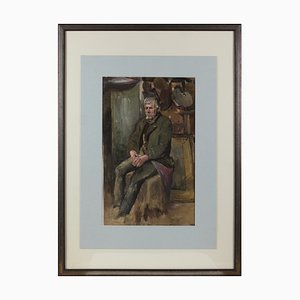

During the Napoleonic occupation, the freedom fighter Florian Geyer was sung about by the Romantics, and the free corps Die Schwarze Schaar, founded in 1813 by Major von Lützow, succeeded the Schwarzer Haufen. It was against this historical background that Gerhard Hauptmann wrote the revolutionary drama Florian Geyer, which premiered at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin in 1896. While the actor Rudolf Rittner, who would later appear in Fritz Lang's films, initially played the role of Schäferhans, he took over the leading role in the new production at Berlin's Lessing Theatre in 1904, again directed by Emil Lessing, which established his fame as an actor. Hauptmann himself praised the acting. He wrote to Hugo von Hofmannsthal: "It went quite well with Florian Geyer. In any case, I had the great pleasure of seeing the play again in an admirable performance". And Lovis Corinth was so taken with Rittner's performance that he painted an oil portrait of him in the role of Florian Geyer in 1906.

After two further graphic versions in 1915 and 1920/21, Corinth returned to the painting a year before his death and almost twenty years after the oil painting to create this graphic version in 1924. Even the inscription in the picture was taken over. This proves all the more the importance of the knight and freedom fighter for Corinth's self-image.

The oil painting, in particular, proclaims the single-minded determination to fight to the last for the values defended, manifested in the oil painting by the tattered flag held out to the enemy. There is a parallel with Rainer Maria Rilke's 1899 story The Cornet, in which the protagonist goes down with the flag that he first saved at the risk of his life.

Consequently, the portrait is also a self-portrait, and the knight's armour is not an academic costume or an ironic refraction, but an expression of Corinth's self-image, which also includes his self-representation as an artist. The Secession poster for the exhibition of his life's work in 1913 depicts Florian Geyer. Art is also a struggle, the will to gain more and more ground through one's work. In this sense, Corinth is an avant-gardist without being part of the avant-garde. He is a lone fighter, not a member of a fighting group - Florian Geyer without his Schwarzem Haufen, all alone. For Corinth, this fight had its own fateful dimension: it was the fight with and against his own body after the paralysis caused by the stroke he suffered in 1911. And if we compare the exemplary oil painting with the late etching, for example the shape of the head or the left arm, the ductus itself seems like a battle event from which the knight emerges. This gives the etching its own artistic quality compared to the oil painting.

About the artist

Determined to become an artist, Corinth entered the Königsberg Art Academy in 1876, where he studied under Otto Günther, who introduced him to Weimar plein-air painting. On Günther's recommendation, Corinth moved to the Munich Art Academy in 1880. There, under the influence of the circle of Leibl and Wilhelm Trübner, he adopted a naturalistic approach to art that was opposed to academic history painting.

After interrupting his studies for a year to do voluntary military service, Corinth went on a study trip to Italy in 1883 and the following year to Antwerp, where he took art lessons from Paul Eugène Gorge. from 1884 to 1887, Corinth stayed in Paris and devoted himself mainly to nude painting at the private Académie Julian.

After a stopover in Berlin, where he met Max Klinger, Walter Leistikow and Karl Stauffer-Bern, Corinth lived in Munich from 1891 to 1901 and became a founding member of the Munich Secession, which was founded in 1892 by Max Liebermann, Otto Eckmann, Thomas Theodor Heine, Hans Olde, Hans Thoma, Wilhelm Trübner, Franz von Stuck and Fritz von Uhde. The Secession gave rise to the Free Association of the XXIV or Munich 24, to which Corinth also belonged.

In 1894, under the tutelage of Otto Eckmann, Corinth learnt the art of etching and, in the field of painting, developed the wet-on-wet style that would characterise his work and lead to the relief-like texture of his paintings.

His relationship with Berlin became more and more intense. When he attended the first exhibition of the Berlin Secession in 1899, he painted a portrait of Liebemann, who in turn painted a portrait of Corinth. After the Munich Secession rejected his painting Salome, he finally moved to Berlin, where the painting was admired at the Secession exhibition and Corinth - through Leistikow - became a much sought-after portraitist.

In 1903 Corinth opened an art school and in 1904 he married his first pupil, Charlotte Berend. His first solo exhibition was organised by Paul Cassirer. In Berlin, Corinth also began to devote himself to the theatre. He worked with Max Reinhardt, designing sets and costumes.

Following Max Liebermann's resignation, Corinth was elected chairman of the Secession in 1911. In the same year, he suffered a stroke that paralysed half of his body. He then devoted himself intensively to graphic art and opened up the field of book illustration.

In 1913, Paul Cassirer organised the first major retrospective of Corinth's work, and in 1918, on his 60th birthday, the Berlin Secession devoted a major exhibition to his work. In 1923, on his 65th birthday, his artistic career was crowned with a extense solo exhibition at the National Gallery.

Even after the 'Freie Sezession' split from the 'Berliner Sezession', Corinth remained in the original association, becoming chairman again in 1915 and professor at the Berlin Academy of Arts the following year.

In 1919, the Corinths purchased the retreat at the Walchensee in Bavaria, which Corinth captured in more than 60 paintings. Corinth died in 1925 on a trip to Amsterdam to see his great idols, Frans Hals and Rembrandt.

Selected Bibliography

Heinrich Müller: Die späte Graphik von Lovis Corinth, Hamburg 1960.

Thomas Deecke: Die Zeichnungen von Lovis Corinth. Studien zur Stilentwicklung, Berlin 1973.

Zdenek Felix (Hrsg.): Lovis Corinth. 1858–1925, Köln 1985.

Karl Schwarz: Das Graphische Werk von / The Graphic Work of Lovis Corinth, San Francisco 1985.

Horst Uhr: Lovis Corinth, Berkeley 1990.

Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: Die Gemälde. Neu bearbeitet von Béatrice Hernad, München 1992.

Peter-Klaus Schuster / Christoph Vitali / Barbara Butts (Hrsg.): Lovis Corinth, München 1996.

Michael F. Zimmermann: Lovis Corinth, München 2008.

Lovis Corinth (1858 Tapiau - 1925 Zandvoort), Rudolf von Rittner come Florian Geyer, 1924 (Müller 854), puntasecca firmata a matita. 20.4 × 14,2 (formato lastra), 37,7 × 30,6 cm (formato foglio). Pubblicato da Karl Nierendorf, Berlino. Incorniciato in un passepartout.

- Impressione forte e precisa. Cornice un po' rovinata e con due piccoli danni.

Esposizione in formato PDF

- L'ultimo uomo in piedi -

Informazioni sull'opera d'arte

Il cavaliere è un leitmotiv dell'opera di Lovis Corinth, che culmina nell'Autoritratto in armatura del 1914. Tra tutti i dipinti su questo tema, Corinth raffigura più spesso Florian Geyer. Discendente da una famiglia nobile della Franconia, lottò per la libertà dei contadini durante le guerre contadine della Riforma, prima diplomaticamente e poi militarmente, guidando le leggendarie Schwarzen Haufen (truppe nere). Il nome deriva dalle uniformi nere con cui Geyer vestiva i contadini disposti a combattere.

Durante l'occupazione napoleonica, il combattente per la libertà Florian Geyer fu cantato dai romantici e il corpo libero Die Schwarze Schaar, fondato nel 1813 dal maggiore von Lützow, succedette agli Schwarzer Haufen. È in questo contesto storico che Gerhard Hauptmann scrisse il dramma rivoluzionario Florian Geyer, che fu presentato per la prima volta al Deutsches Theater di Berlino nel 1896. Mentre l'attore Rudolf Rittner, che in seguito sarebbe apparso nei film di Fritz Lang, interpretò inizialmente il ruolo di Schäferhans, egli assunse il ruolo di protagonista nella nuova produzione al Teatro Lessing di Berlino nel 1904, sempre con la regia di Emil Lessing, che sancì la sua fama di attore. Lo stesso Hauptmann ne lodò la recitazione. Scrisse a Hugo von Hofmannsthal: "Con Florian Geyer è andata abbastanza bene. In ogni caso, ho avuto il grande piacere di rivedere l'opera in un'interpretazione ammirevole". Lovis Corinth fu talmente colpito dall'interpretazione di Rittner da dipingere un ritratto a olio di lui nel ruolo di Florian Geyer nel 1906.

Dopo due ulteriori versioni grafiche nel 1915 e nel 1920/21, Corinth tornò sul dipinto un anno prima della sua morte e quasi vent'anni dopo il dipinto a olio per creare questa versione grafica nel 1924. Anche l'iscrizione nel quadro è stata ripresa. Ciò dimostra ancora di più l'importanza del cavaliere e del combattente per la libertà per l'immagine di Corinto.

Il dipinto a olio, in particolare, proclama la determinazione assoluta a combattere fino all'ultimo per i valori difesi, manifestata nel dipinto a olio dalla bandiera a brandelli tesa al nemico. C'è un parallelo con il racconto La cornetta di Rainer Maria Rilke del 1899, in cui il protagonista affonda con la bandiera che ha salvato a rischio della sua vita.

Di conseguenza, il ritratto è anche un autoritratto e l'armatura del cavaliere non è un costume accademico o una rifrazione ironica, ma un'espressione dell'immagine di sé di Corinto, che comprende anche la sua auto-rappresentazione come artista. Il manifesto della Secessione per l'esposizione delle opere della sua vita nel 1913 raffigura Florian Geyer. L'arte è anche una lotta, la volontà di guadagnare sempre più terreno attraverso il proprio lavoro. In questo senso, Corinth è un avanguardista senza far parte dell'avanguardia. È un combattente solitario, non un membro di un gruppo di lotta - Florian Geyer senza il suo Schwarzem Haufen, tutto solo. Per Corinth, questa lotta aveva una sua dimensione fatale: era la lotta con e contro il suo stesso corpo dopo la paralisi causata dall'ictus che lo colpì nel 1911. E se confrontiamo l'esemplare dipinto a olio con l'incisione tardiva, ad esempio la forma della testa o del braccio sinistro, il ductus stesso sembra un evento di battaglia da cui emerge il cavaliere. Questo conferisce all'acquaforte una qualità artistica propria rispetto al dipinto a olio.

Informazioni sull'artista

Deciso a diventare un artista, Corinth entra all'Accademia d'arte di Königsberg nel 1876, dove studia sotto la guida di Otto Günther, che lo introduce alla pittura plein air di Weimar. Su raccomandazione di Günther, Corinth si trasferisce all'Accademia d'arte di Monaco nel 1880. Qui, sotto l'influenza del circolo di Leibl e Wilhelm Trübner, adottò un approccio naturalistico all'arte che si opponeva alla pittura storica accademica.

Dopo aver interrotto gli studi per un anno per prestare servizio militare volontario, Corinth compie un viaggio di studio in Italia nel 1883 e l'anno successivo ad Anversa, dove prende lezioni d'arte da Paul Eugène Gorge. Dal 1884 al 1887, Corinth rimane a Parigi e si dedica principalmente alla pittura di nudo presso l'Académie Julian privata.

Dopo una sosta a Berlino, dove incontra Max Klinger, Walter Leistikow e Karl Stauffer-Bern, Corinth vive a Monaco di Baviera dal 1891 al 1901 e diventa membro fondatore della Secessione di Monaco, fondata nel 1892 da Max Liebermann, Otto Eckmann, Thomas Theodor Heine, Hans Olde, Hans Thoma, Wilhelm Trübner, Franz von Stuck e Fritz von Uhde. La Secessione diede origine alla Libera Associazione dei XXIV o Monaco 24, di cui faceva parte anche Corinto.

Nel 1894, sotto la tutela di Otto Eckmann, Corinth apprende l'arte dell'incisione e, nel campo della pittura, sviluppa lo stile bagnato su bagnato che caratterizzerà il suo lavoro e che porterà alla texture a rilievo dei suoi dipinti.

Il suo rapporto con Berlino si fa sempre più intenso. Quando partecipa alla prima mostra della Secessione di Berlino nel 1899, dipinge un ritratto di Liebemann, che a sua volta dipinge un ritratto di Corinto. Dopo che la Secessione di Monaco rifiutò il suo dipinto Salomè, si trasferì infine a Berlino, dove il quadro fu ammirato alla mostra della Secessione e Corinto - attraverso Leistikow - divenne un ritrattista molto richiesto.

Nel 1903 Corinth apre una scuola d'arte e nel 1904 sposa la sua prima allieva, Charlotte Berend. La sua prima mostra personale fu organizzata da Paul Cassirer. A Berlino, Corinth inizia a dedicarsi anche al teatro. Lavora con Max Reinhardt, disegnando scenografie e costumi.

Dopo le dimissioni di Max Liebermann, Corinth fu eletto presidente della Secessione nel 1911. Nello stesso anno fu colpito da un ictus che gli paralizzò metà del corpo. Si dedica quindi intensamente all'arte grafica e apre il campo dell'illustrazione di libri.

Nel 1913, Paul Cassirer organizza la prima grande retrospettiva dell'opera di Corinth e nel 1918, in occasione del suo 60° compleanno, la Secessione di Berlino gli dedica una grande mostra. Nel 1923, in occasione del suo 65° compleanno, la sua carriera artistica fu coronata da un'ampia mostra personale alla National Gallery.

Anche dopo la scissione della "Freie Sezession" dalla "Berliner Sezession", Corinth rimase nell'associazione originaria, diventando nuovamente presidente nel 1915 e professore all'Accademia delle Arti di Berlino l'anno successivo.

Nel 1919, i Corinth acquistarono il ritiro sul Walchensee in Baviera, che Corinth immortalò in più di 60 dipinti. Corinth morì nel 1925 durante un viaggio ad Amsterdam per vedere i suoi grandi idoli, Frans Hals e Rembrandt.

Bibliografia selezionata

Heinrich Müller: Die späte Graphik von Lovis Corinth, Amburgo 1960.

Thomas Deecke: Die Zeichnungen von Lovis Corinth. Studien zur Stilentwicklung, Berlino 1973.

Zdenek Felix (Hrsg.): Lovis Corinth. 1858-1925, Colonia 1985.

Karl Schwarz: Das Graphische Werk von / The Graphic Work of Lovis Corinth, San Francisco 1985.

Horst Uhr: Lovis Corinth, Berkeley 1990.

Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: Die Gemälde. Neu bearbeitet von Béatrice Hernad, München 1992.

Peter-Klaus Schuster / Christoph Vitali / Barbara Butts (Hrsg.): Lovis Corinth, München 1996.

Michael F. Zimmermann: Lovis Corinth, München 2008.

Contattaci

Fai un'offerta

Abbiamo notato che sei nuovo su Pamono!

Accetta i Termini e condizioni e l'Informativa sulla privacy

Contattaci

Fai un'offerta

Ci siamo quasi!

Per seguire la conversazione sulla piattaforma, si prega di completare la registrazione. Per procedere con la tua offerta sulla piattaforma, ti preghiamo di completare la registrazione.Successo

Grazie per la vostra richiesta, qualcuno del nostro team vi contatterà a breve.

Se sei un professionista del design, fai domanda qui per i vantaggi del Programma Commerciale di Pamono