The Uprising of Postmodern Design Today

Memphis Calling

-

Memphis designers' portrait with Masanori Umeda's Tawaraya Bed, 1981

<i>Courtesy Memphis Post Design Gallery; Photo © Studio Azzurro</i>

-

Print All Over Me, 2014

<i>Photo © Michael Burk</i>

-

Nathalie Du Pasquier: Royal Sofa, 1983

<i>Courtesy Memphis Post Design Gallery; Photo © Studio Azzurro</i>

-

Nathalie Du Pasquier: Collection for American Apparel, 2014

<i>Courtesy of American Apparel</i>

-

Nathalie du Pasquier: Cushion for Wrong for Hay, 2014

<i>Courtesy of Wrong for Hay</i>

-

Nathalie Du Pasquier: detail of Burundy, 1981

<i>Courtesy Memphis Post Design Gallery; Photo © Also Ballo, Guido Cegani, Peter Ogilvie</i>

-

Installation detail from Sight Unseen Offsite, 2014

<i>Photo © Mike Vorrasi</i>

-

Masanori Umeda: Ginza, 1982

<i>Courtesy Memphis Post Design Gallery; Photo © Studio Azzurro</i>

-

Peter Shire: Bel Air, 1982

<i>Courtesy Memphis Post Design Gallery; Photo © Studio Azzurro</i>

-

Bethan Laura Wood at Aram Gallery, London, 2013

<i>Photo © Fernando Laposse</i>

-

Wood's ZigZag: CrissCross show at Aram Gallery, London, 2013

<i>Photo © Fernando Laposse</i>

-

Nathalie Du Pasquier and Bethan Laura Wood in conversation

<i>Photo © Fernando Laposse</i>

-

Bethan Laura Wood: Seamless Fabric, 2010

<i>© Bethan Laura Wood</i>

-

Nicole Cherubini: Astralogy, 2013

<i>Photo © Jason Mandella</i>

-

Misha Kahn: Saturday Morning: Standing Blue Mirror, 2013

<i>Photo © Clemens Kois</i>

-

Peter Shire: Colorado, 1983

<i>Courtesy Memphis Post Design Gallery; Photo © Lucien Schweitzer et Editions</i>

-

Martine Bedin: Super, 1981

<i>Courtesy Memphis Post Design Gallery; Photo © Lucien Schweitzer et Editions</i>

-

Ohad Mermomi: The Working Day, 2012

<i>Photo © Silvia Ross</i>

-

François Chambard & UM Project: Pink Perch (from Odd Harmonics), 2013

<I>Courtesy Judith Charles Gallery</i>

-

Michele de Lucchi: Oceanic, 1981

<i>Courtesy Memphis Post Design Gallery; Photo © Silvia Ross</i>

-

DAMM: Memphis, 2013

<i>Courtesy of DAMM & L'ArcoBaleno</i>

-

Jonathan Zawada: Affordances Tables, 2013/2014

<i>Courtesy of Matter & L'ArcoBaleno</i>

-

Misha Kahn: Geometrics, Figures and Solids Table, 2013

<i>Photo © Clemens Kois</i>

-

Peter Shire: Peninsula, 1982

<i>Courtesy Memphis Post Design Gallery; Photo © Studio Azzurro</i>

-

Portmanteau and Alchemy Spirit Altar Candelabra by Material Lust

<i>Photo © Material Lust</i>

When Ettore Sottsass gathered a group of fellow designers together in 1980, his aim was grand: a revolution against the sober functionalism of modernist-era design. While the collective’s ambitions were impressive, their name was simply derived; Bob Dylan’s “Stuck Inside Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again” happened to be playing in the background the day they joined forces. Thousands of miles away from Tennessee and Dylan, the Milan-based Memphis Group developed one of the most recognizable styles of the late 20th century, predicated on the converging influences of Pop Art, popular culture, and Art Deco.

In stark contrast to the restrained aesthetics that had reigned for decades, Sottsass and his colleagues invented a visual vocabulary that was characterized by playful, geometrically driven forms expressed in artificial materials, brash proportions, riotous palettes, and cheeky prints reminiscent of Keith Haring’s madcap murals. Master of minimalism Jasper Morrison summed up a common response to early encounters with Memphis’s maximalism when he said, “It was the weirdest feeling… You were in one sense repulsed by the objects, or I was, but also immediately freed by the sort of total rule-breaking.”

Early acceptance from the fashion and arts communities made the work of Memphis designers like Nathalie du Pasquier and Peter Shire highly collectible, and their pieces found their way into the homes of influencers like Karl Lagerfeld and Max Palevsky. Despite its popularity among the era’s tastemakers, Memphis’s moment in the limelight was short-lived. Recently, however, the style they championed is in the midst of a major and much talked about revival, thanks to a new crop of designers who are finding fresh inspiration in the audacious spirit of Sottsass’s clan.

The trend has been burning brightly all over New York design shows—like Collective Design Fair and the Museum of Art & Design’s Biennial—but felt particularly poignant at last spring’s Salone del Mobile, which kicked off with the largest Memphis retrospective in Milan to date, entitled La Collezione Memphis alle Stelline at Galleria Gruppo Credito Valtellinese. A few weeks later, during New York Design Week, Sight Unseen’s Offsite exhibition drove the point home, especially in the projects developed by digital customization company Print All Over Me, which encouraged designers like Fort Standard and Snarkitecture to create their own prints and apply them to their furniture and fashion collections.

Like the first manifestation of the Memphis style, the resurgence today feels at once sudden and organic like an existentialist’s reaction to a stale environment—on the other hand the current movement is less cohesive, randomly permeating the work of young designers as far flung as Bethan Laura Wood in London and Aussie-native Jonathan Zawada in L.A. Though acting as individuals, those influenced by Memphis seem to share a propensity for crafting wild works in the face of an industry that has turned increasingly towards the homogenous and mass-produced. “We are at a confluence of postmodern aesthetics, the wealth and taste of a late empire, and the means of production being scaled down and accessible to everyone. This is a great recipe for unique design,” explains Brenda Zurn, one of the designers behind Damm Studio in St. Petersburg, Florida. “As a result, there seems to be a growing number of young designers who are making what they want to make and not being so concerned with fitting into a design industry.”

“The Memphis Group created work based on attitude not rationality,” says Lauren Swafford, one half of the New York-based duo Material Lust, whose gothic collection of metal designs debuted at Offsite. “Like the Memphis designers, our work isn't built on functionality but rather in favor of having a presence, a mood, a reaction. Our goal is to make furniture that is symbolically dense.” Swafford is not alone; other designers like Misha Kahn—whose whimsical furniture appeals to emotions rather than necessity—are also picking up on this philosophical break from the conventional obsession with functionality and using it as a springboard for their own work.

Radical in its own time, Memphis’s counterculture ethos seems to be at the heart of what appeals most to this new rebellious generation—potentially aided by a subconscious nostalgia for childhood touchstones like Pee Wee’s Playhouse, David Bowie, and Saved by the Bell, all of which shared in the rambunctious spirit of the Memphis designers. “I find Memphis inspiring because of its boldness in setting forth a point of view. I remember as a child seeing a Memphis piece and not liking it at all; it was too much, too full on,” explains designer Bethan Laura Wood, who’s own work often re-contextualizes everyday elements with unexpected colors and prints. “But as I grew up, I found that I was drawn more and more to their works, as I loved their ability to combine pattern and color in a way that was playful but not childish.”

Material selection may be the most obvious distinction between the original Memphis movement and this latest iteration. Unlike the Memphis designers who used newly available laminates to mimic wood, marble, and other materials in order to create their hyper of-the-moment pieces, designers like Damm Studio and Jonathan Zawada are utilizing cutting-edge techniques to transform traditional materials into something that feels unmistakably contemporary. Pieces like Damm’s collection of Memphis lamps, whose flexible gooseneck bulbs appear to almost sprout out of their wood and marble bases, exemplify the way young designers are blending high technology with chunky aesthetics. The result of these works is a fascinating mélange of optimistic futurism and nostalgia that feels authentic both in relation to today and to the Memphis Group’s playful vision of the future.

Du Pasquier—the defacto celebrity for this second Memphis wave thanks to her recent capsule collections for American Apparel and Wrong for Hay, both of which featured her iconic prints—echoes this sentiment. “Every generation orients itself relative to the past,” says du Pasquier. “Maybe today people look at Memphis because it seems to have been the first very media-driven design movement before the Internet.” But, as Wood notes, “It feels that with the Internet the norm changes so fast, within a year something can go from breaking the norm to being it.” Were Sottsass alive today, this is a feeling he would undoubtedly identify with.

-

Text by

-

Kat Herriman

Kat is a New York writer who loves art, design, and social awkwardness.

-

Scopri altri prodotti

Rulla di Mario Milana

M di Mario Milana

Poltrona mm3 gialla di Mario Milana

mm1 di Mario Milana

Centrotavola vintage di Studio Superego

Portacandele Alia Pack B di HALA, 2017

Portacandele Alia Pack A di HALA, 2017

Tavolino Vima di HALA, 2016

Lampada da terra Vilma di HALA, 2016

Totem 3 di Anthony Bianco per Bianco Light & Space, 2017

Totem 2 di Anthony Bianco per Bianco Light & Space, 2017

Totem 1 di Anthony Bianco per Bianco Light & Space, 2017

Mobiletto Truecolors di Visser & Meijwaard

Credenza Truecolors di Visser & Meijwaard

Panca Truecolors di Visser & Meijwaard

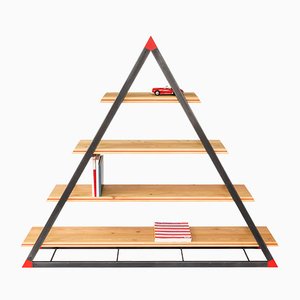

Libreria NOON triangolare di Dozen Design

Sgabello Truecolors di Visser & Meijwaard

Comodino Truecolors di Visser & Meijwaard

Portachiavi Juvent in ottone di Dozen Design

Specchio WOW triangolare giallo di Dozen Design

Tavolini da caffè in bronzo di Studio Superego, set di 3

Specchio WOW triangolare turchese di Dozen Design

Specchio WOW triangolare rosa di Dozen Design

Lapis Lazuli Lamp by Studio Superego

DNA Cast Acrylic di Studio Superego per Poliedrica

Lampada da tavolo Bubbles di Studio Superego per Poliedrica

Portacandele Alia Pack C di HALA, 2017

Print All Over Me at Sight Unseen Offsite 2014

Photo © Mike Vorrasi

Print All Over Me at Sight Unseen Offsite 2014

Photo © Mike Vorrasi

Portrait of Ettore Sottsass by Bruno Gecchelin, 1974. From Sottsass, Phaidon Press

Photo © Bruno Gecchelin

Portrait of Ettore Sottsass by Bruno Gecchelin, 1974. From Sottsass, Phaidon Press

Photo © Bruno Gecchelin